How did we end up with the current alphabet?

According to Rev. Samuel Johnson (the author of “The History of the Yorubas from the Earliest Times to the Beginning of the British Protectorate”)...

“After several fruitless efforts had been made either to invent new characters, or adapt the Arabic, which was already known to Moslem Yorubas, the Roman character was naturally adopted, not only because it is the one best acquainted with, but also because it would obviate the difficulties that must necessarily arise if missionaries were first to learn strange characters before they could undertake scholastic and evangelistic work. With this as basis, special adaptation had to be made for pronouncing some words not to be found in the English or any other European language.”

There you have it! We ended up with the Latin script because it would be easy for the Europeans to learn!

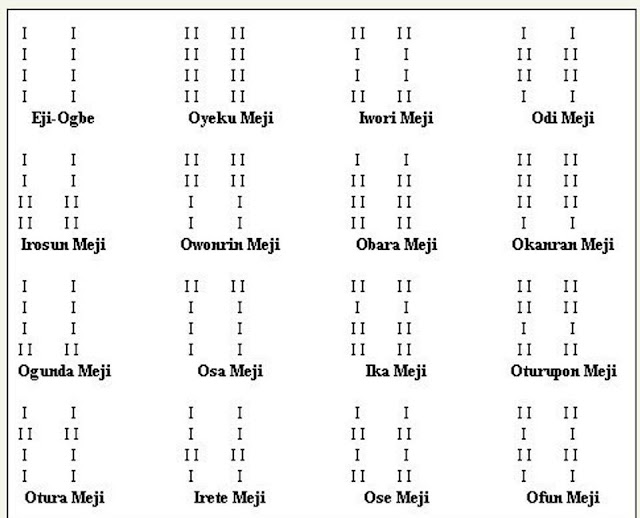

Bishop Samuel Ajayi Crowther will forever be remembered for his great service to the Yoruba Nation by creating the alphabet. Nevertheless, with today's technology and new knowledge in Orthography, we can create a better alphabet based on Odù Ifá that will best reflect the tonal nature of the language.

Bishop Samuel Ajayi Crowther will forever be remembered for his great service to the Yoruba Nation by creating the alphabet. Nevertheless, with today's technology and new knowledge in Orthography, we can create a better alphabet based on Odù Ifá that will best reflect the tonal nature of the language.

A new alphabet will allow us to do away with the diacritics (àmìn òkè, àmìn ìsàlẹ̀). The current alphabet has only 25 characters, with Odù Ifá, we have 256 to choose from! Better still, we can ditch alphabets altogether and go for logograph just like the Chinese and Japanese.

Over to Yoruba linguists and orthographers to take this forward. Check the following links for inspiration…

Graphics sourced from Wikipedia.